Neurodiversity and libraries

Terms, tools and strategies for creating more inclusive experiences for staff and patrons

Special thanks to Kate James, Program Coordinator for Metadata Engagement at OCLC, and to Renee Grassi, Accessibility Consultant and Librarian, for their review of this resource.

CC BY-SA 4.0

In recent years, society has focused more on neurodiversity—for example, you hear it mentioned in popular media and movies, as more diverse characters are represented in mainstream media. New research has led to an expanded understanding of neurodiversity, leading to later-in-life diagnoses and prompting growing advocacy, especially on social media platforms. These shifts in awareness and acceptance have sparked changes in schools, workplaces, and public spaces. Efforts to understand and appreciate neurodiversity have made it into mainstream culture, and we want to highlight some resources that may help you better support your fellow staff members and patrons.

Also check out this WebJunction webinar with Renee Grassi, Embracing neurodiversity: Cultivating an inclusive workplace for neurodivergent staff.

Definitions

First, some definitions:

- Neurodiversity is a concept that recognizes and celebrates the natural variation of human brains.

- Neurotypical refers to individuals with cognitive functioning that aligns with societal norms.

- Neurodiverse or neurodivergent describes individuals whose cognitive functioning differs from what is considered typical or neurotypical.

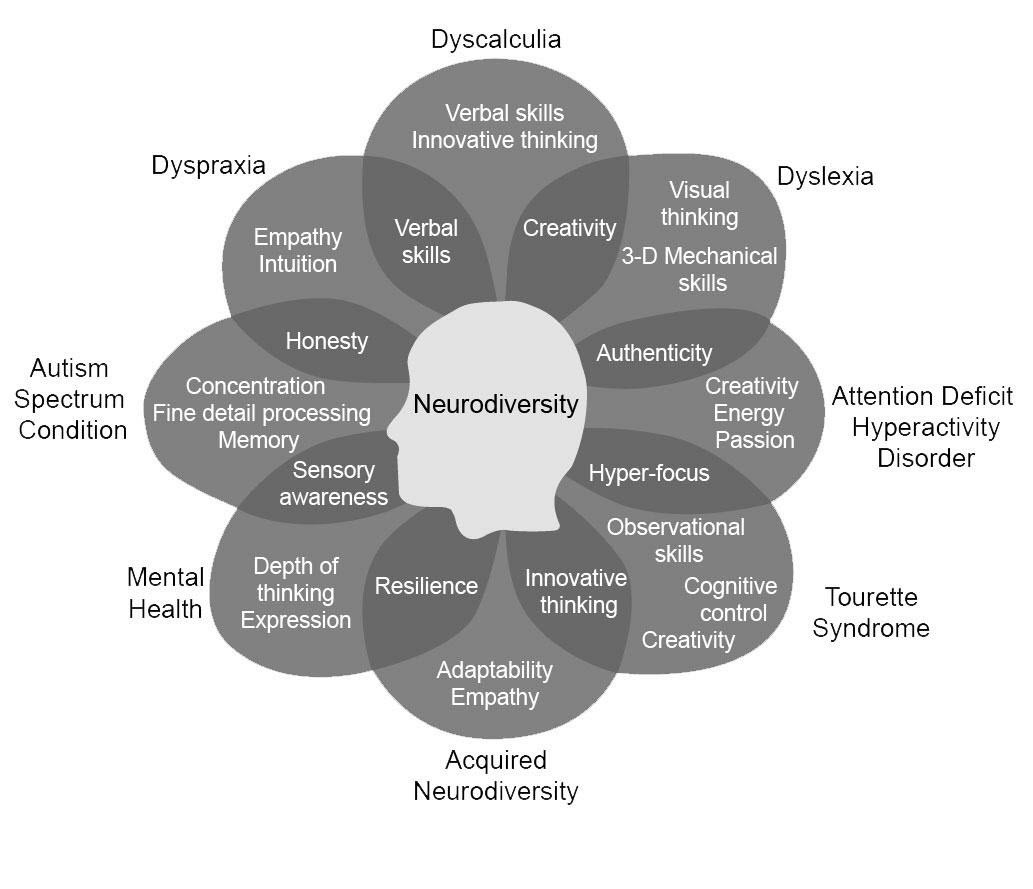

- The term neurodiversity is an umbrella term that refers to a wide variety of disabilities and conditions, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), ADHD, dyslexia, dyspraxia or developmental coordination disorder (DCD), dyscalculia (difficulty learning or comprehending arithmetic), Tourette Syndrome, PTSD, traumatic brain injuries, and mental health conditions such as bipolar and OCD.

These terms are not universally agreed upon, and terminologies often change over time so it’s good to check to see what terminology is currently in use. Additionally, there are two schools of thought about how to refer to the individuals we’re discussing. People who favor identity-first language, e.g. neurodivergent individuals, often feel a sense of empowerment around their disability and do not view it as an impairment. People who favor person-first language, e.g. a person who is neurodiverse, want to emphasize the humanity of themselves or their children before any label is attached. We want to acknowledge the debate while embracing the fact that there is not a perfect solution. In individual interactions, it’s best to ask the person what they prefer. For more information on person first vs identity first language see Words Matter, an ACLS blog post by Renee Grassi.

An invisible disability is a physical, mental, or neurological condition that is not visible from the outside, yet can limit or challenge a person’s movements, senses, or activities. The very fact that these symptoms are invisible can lead to misunderstandings, false perceptions, and judgments, and people experiencing an invisible disability need to self-identify to receive accommodations. Invisible disabilities are now more often referred to as “non-apparent disabilities” because the phrase “invisible” is ableist. It relies on the sense of sight in order to determine if someone has a disability or not.

Prevalence

It is estimated that 15-20% of the world’s population is neurodiverse, and 3.7 percent of library staff in the United States and 5.9% in Canada have some form of neurodiversity. But there’s a lot more nuance to prevalence when discussing neurodiversity. Experts recognize that surveys and studies rely on self-reported data, that not everyone has access to diagnostic tools and evaluations and that these tools and surveys are often built, consciously or unconsciously, with bias. Disability is viewed differently in different cultures, due to varied stigmas and misinformation, and some may not opt to self-identify as neurodivergent. The umbrella of what is considered neurodiverse is broad, and it’s a personal decision based on an individual’s experience.

Neurodivergence: Strengths and characteristics

Taking a strength-based approach, it’s useful to understand the benefits of neurodiversity from this Wisconsin Public Library Systems presentation by Renee Grassi, Cultivating an inclusive workplace for neurodivergent staff. Neurodiversity is a broad term, encompassing a wide range of individuals. Note that this list is not all-encompassing or inclusive of every characteristic.

- Innovative and out-of-the-box thinkers

- Creative and imaginative

- Technical and design strengths

- New ways to solve problems

- Challenges norms and seeks improvement

- High levels of concentration

- Keen accuracy and ability to detect errors

- Pattern recognition and finding connections

- In tune with their environment and surroundings

- Strong recall of information and detailed factual knowledge

- Reliability and persistence

- Ability to excel at work that is routine or repetitive in nature

- Highly empathetic

To learn more, this article describes how neurodivergent co-workers can boost productivity and innovation.

From a workplace perspective, it is also helpful to understand some of the areas where neurodivergent thinkers may work differently:

- Challenges with time management, task management, multitasking, initiating activities or tasks, prioritizing and planning alongside the ability to focus deeply

- Communication style and differences, including interrupting others or blurting out, difficulty reading non-verbal cues, literal interpretations

- Information processing, including challenges generating ideas independently experiencing information overload

- Emotional fatigue and sensory challenges and overwhelm. This video helps explain to neurotypical individuals what sensory overload is like.

To get a perspective from a librarian who has autism, read an interview with Charlie Remy, an academic librarian who discusses his own experience and what others can do to create a more inclusive profession.

Accessibility benefits everyone

ACRL’s Keeping up with neurodiversity brief contains great information about how disability accommodations actually benefit everyone, including a description of the Curb-Cut Effect. For example, a ramp built for wheelchair accessibility in turn makes deliveries easier too. Things that would commonly be seen as accommodations in educational spaces—such as providing clear written directions and video transcripts or offering sensory-sensitive environments—are tools that can help all people succeed, regardless of their neurotype.

Another term that is useful is the concept of Universal Design—"an approach to design that is meant to produce buildings, products, and environments that are accessible to virtually everyone, without the need for adaptation or specialized design, regardless of ability or age" (defined by the Invisible Disability Project). The Universal Design for Learning Guidelines help improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people. The guidelines assist in thinking about how to make your library welcoming to neurodiverse staff and patrons.

Ways to transform your library to welcome neurodiverse staff

Adopting an intentional approach to workplace culture can create a more inclusive environment for neurodiverse staff and foster a positive and productive space for all employees. This can look like rethinking meeting structures, reflecting on how to communicate and engage with one another, and considering how to respond when challenges crop up. Here are some resources and strategies that can help inform your library’s approach.

- Transforming librarianship to model neuroinclusion in libraries: This webinar introduces participants to the neurodiversity employment movement and its impact in other fields, such as IT. The presenters share results from an IMLS-funded initiative, Neurodiversity and Employment, that highlights the voices of neurodivergent librarians and their journey of negotiating identity as they face barriers and enablers to their success. Among other topics, the webinar has information for leaders who want to create a culture that is inclusive. The Neurodiversity@Work Playbook is the latest resource created through the initative.

- Victoria Tretis offers A neuroinclusive approach to virtual meetings which has some useful pointers such as thinking through the need to be on camera. For some neurodiverse folks this can be stressful due to the intense eye contact and the worry about how their stimming will be perceived.

- Cultivating a welcoming workplace for neurodivergent staff (pdf) Renee’s Grassi’s presentation offers excellent tips for managers and supervisors who seek to create a welcoming environment for all staff. She includes tips for inclusive hiring, policies, onboarding, strategies for teams, and ways to offer support.

- For adults with ADHD, time blindness is the inability to sense how much time has passed and estimate the time needed to get something done. In a work environment, this can lead to missed meetings and rushed deadlines among other things. Strategies like setting timers and using app-blockers can help. Normalizing these practices and having tolerance as co-workers find strategies to assist them can help.

- A Community of Care: We recently learned about the concept of a conference embracing "A Community of Care" which involved being very upfront about communicating accommodations that would be offered and expected to make the space work for as many attendees as possible.

Accommodations are important, and accessibility makes a difference. But inclusion happens when we systemically tear down the barriers to employment and success.

It's also useful to distinguish between accommodations, accessibility, and inclusion. This scenario offered by Ludmila Praslova in her Forbes article is helpful. A library introduces flexible working hours. In the back office, there are quiet zones for employees who struggle with noise and sensory overload. But if neurodivergent employees still face subtle (or not-so-subtle) stigmas and are excluded from high-stakes projects and leadership development, the company’s efforts toward inclusion still fail.

Neuroinclusion goes deeper than surface fixes. It means that the organization has mechanisms for ensuring that neurodivergent people don’t just “function” but are valued, supported in their development goals, and recognized for their contributions.

— Ludmila Praslova

Ways to transform your library to welcome neurodiverse patrons

In the spirit of being welcoming to all, library staff can make some adjustments to help neurodiverse patrons feel like they belong.

- A research team at the University of Washington has published an Autism-Ready Libraries Toolkit that seeks to “empower youth-serving librarians and library staff with the early literacy training and programming materials they need to provide autism-inclusive early literacy services.” The toolkit contains three modules to support staff in delivering autism-inclusive programming. Milly Romeijn-Stout, a researcher on the project, hopes library staff see that “even small changes can improve access for autistic children and their families and make a big impact on the whole community.” You can learn more about the toolkit in this WebJunction article, Helping libraries to be autism-ready.

- Renee Grassi provides encouraging tips (pdf) in her presentation for the Wisconsin Public Library Systems, applicable here as well. For example, is your signage concise and literal? Could you add images to go with text? Do staff who are responsible for programming think about ways to make the activity accessible to a range of participants, e.g. Are there multi-sensory options that are normalized?

- Amanda Boyer and Amir El-Chidiac offer lessons from their experiences making Susquehanna University’s Library more accessible to neurodiverse students including having an occupancy counter so users can time their visits based on how crowded the library is.

- The Neurodiversity Design System offers some excellent guidelines and principles informed by the needs of neurodiverse users and learners.

We hope these resources help you better support staff members and patrons. We know this field is expanding and realize definitions and best accepted practices change so please let us know if you see updates. Reach us at via [email protected] or find us on Facebook. And be sure to join us on Tuesday, 4 March, 2025, for a WebJunction webinar with Renee Grassi, Embracing neurodiversity: Cultivating an inclusive workplace for neurodivergent staff.

Resources

Articles, blogs, and other reading

Learn more about neurodiversity

- ADHD time blindness: How to detect it & regain control over time – Attention Deficit Disorder Association

- Identity-first language – by Lydia Brown, Autism Self-Advocacy Network

- Words Matter – ACLS blog post by Renee Grassi

- Keeping up with… neurodiversity – ALA/ACRL

- Neurodistinct vs neurodivergent vs neurospicy: Decoding the evolution – focus bear

- What does it mean to be neurodivergent? – Verywell mind

- What is an invisible disability? – Invisible Disabilities Association

- The Autistic's Guide to Self-Discovery: Flourishing as a Neurodivergent Adult – Sol Smith

- Divergent Mind: Thriving in a World That Wasn't Designed for You – Jenara Nerenberg

- A Thousand Ways to Pay Attention: a Memoir of Coming Home to My Neurodivergent Mind – Rebecca Schiller

- Neurotribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity – Steve Silberman

Neurodiversity in the library

- Helping libraries to be autism-ready – WebJunction article featuring the Autism-Ready Libraries Toolkit

- Come chill out at the library: Creating soothing spaces for neurodiverse students. – Amanda Boyer and Amir El-Chidiac, Journal of new Librarianship

- Hopkinton Public Library unites community in library planning – WebJunction article featuring a new library sensory room

- Library Workers Who are Neurodivergent, Part One and Part Two – Kelley Mc Daniel, ALA/APA

- Neurodiversity in the Library: One librarian’s experience – Interview with Charlie Remy, In the library with the lead pipe

- Webinar Series: Neurodiversity at Work, Wisconsin Public Library Systems including, Cultivating an inclusive workplace for neurodivergent staff (pdf), – Renee Grassi

- Libraries are for everyone! Except if you’re autistic – Alissa McCulloch, Cataloguing the Universe

- My Turn: Neurodivergence in Libraries – Alex Towers, Illinois Library Association, ILA Reporter

Neurodiversity and learning

- 5 tips for working with neurodivergent adult learners – ABC Life Literacy Canada

- How can I best teach neurodiverse adult learners? – Walt Hansmann

- Keeping up with... universal design for learning – ALA/ACRL

Neurodiversity in the workplace

- Autism doesn’t hold people back at work. Discrimination does – Harvard Business Review

- Neurodivergent employees boost productivity and innovation in the workplace. Is yours reaping the benefits? – Spring Health

- Neurodiversity at work: a Biopsychosocial model and the impact on working adults – Nancy Doyle, Oxford University Press

- Neurodiversity At Work: Neuroinclusion > Accessibility > Accommodations – Ludmila Praslova, Forbes

- A neuroinclusive approach to virtual meetings – Victoria Tretis

- Supporting neurodiversity in the library workplace – Bobbi Newman

- Neurodiversity at Work: Drive Innovation, Performance and Productivity with a Neurodiverse Workforce – Theo Smith and Amanda Kirby

- The Neurodiverse Workplace: an employer's guide to managing and working with neurodivergent employees, clients and customers – Victoria Honeybourne

Webinars and videos

- Register now for the March 4 WebJunction webinar with Renee Grassi, Embracing neurodiversity: Cultivating an inclusive workplace for neurodivergent staff

- Neurodiversity at work – Webinar series, Wisconsin Public Library Systems

- Sensory overload video – This video helps explain to neurotypical individuals what sensory overload is like. Neurodivergent people may be sensory seekers or sensory avoiders. For sensory avoiders, the normal sounds of a workplace can be overwhelming, so some choose to wear headphones to reduce the noise to a tolerable level.

- Included: Neurodiversity and disability in libraries – Kent State University College of Communication and Information webinar. Collaborators: Dr. Amelia Gibson, UMD College of Information Studies; Renee Grassi, Director Lake Bluff Public Library; Kent State University's Student Chapter of ALA and Graduate Student Advisory Council; University of Pittsburgh's Student Chapter of ALA.

- Transforming librarianship to model neuroinclusion in libraries – Library Accessibility Alliance

- Strategies for Success for Neurodiverse Librarians – Colorado State Library

Other resources

Toolkits, projects, guidelines, and standards

- Initiative for Neurodiversity and Employment at the University of Washington iSchool, including Autism-Ready Libraries and the Autism-Ready Libraries Toolkit, as well as The Neurodiversity@Work Playbook.

- Conference page for Community of Care – ARL Library Assessment Conference. Learn about this effort to co-create a community of care to support the individual and collective needs of the group at the conference.

- Neurodiversity Design Standards – The NDS is a coherent set of standards and principles that combine neurodiversity and user experience design for Learning Management Systems. Design accessible learning interfaces to support success and achievement for everyone.

- The Practice Model for an Equitable Workplace Transition Program (EWTP): Disability and Neurodiversity – IMLS project

- Project ENABLE, including resources for Universal Design in learning

Support networks

- Autistics in Libraries & Their Allies – Facebook group

- Neurodivergent Library and Information Staff Network – Supporting Neurodivergent Talent in Library and Information Staff in the UK & Ireland. See resources and outputs.