Taking the Plunge into Prototyping

Editor’s note: The Small Libraries Create Smart Spaces project used placemaking and design-thinking strategies to support libraries through a process that transformed their existing spaces in cost-effective ways and reimagined their relationship with their communities. The series of stories that follow summarizes the experiences of the second Smart Spaces cohort, who participated in 2019-2020. This third story in the series discusses the “prototyping” phase of the design thinking process. For stories of the first cohort (2017-2018), see their Transformation Stories.

After opening up a world of possibilities with community discovery and ideation brainstorming, the Small Libraries Create Smart Spaces libraries were ready to move on to the next step in the design thinking process: prototyping. Creating a prototype is a great way to bring an idea out of your head and into a tangible, physical reality. Prototyping is an opportunity to test, revise, and test again before committing dollars and resources to a project. A prototype doesn’t have to be complicated or high tech; creating a small-scale model of your idea with materials like paper, cardboard, LEGOs, or other crafting materials can be an effective way to visualize and test your proposed transformation.

The Smart Spaces participants were instructed to select one idea to carry forward from brainstorming into implementation and stage a prototype to test that idea. They were asked to consider key questions to test through prototyping, such as:

- Is there enough room for the furnishings you envision and the users of the space?

- What are you most curious about in terms of how users will behave in the space or how they will interact with the resources?

- Do you want to experiment with color, design, or arrangement of furnishings?

- Where do you think the concept might be weakest and what would you like to learn to make it better?

Prototyping is another phase of design thinking that can feel like a stretch outside of one's comfort zone. Once the Smart Spaces cohort realized that there’s no need to be high-tech or polished, however, they forged ahead. After gathering materials, participants created a variety of prototypes, proving there is no right or wrong way to create and that some of the best inspiration can come from the least expected places.

Examples from the Field

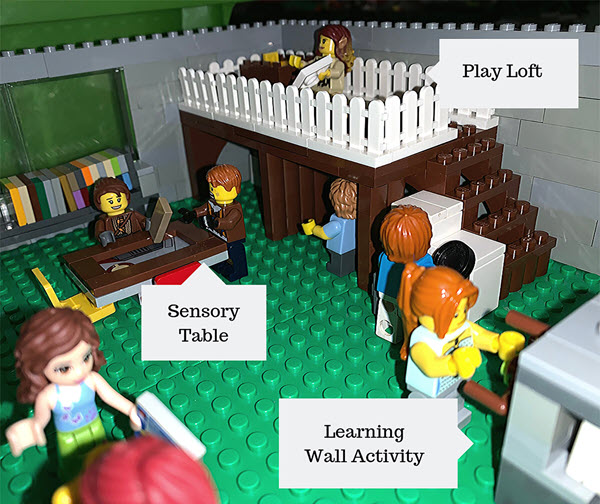

Show Us Your LEGOs in Show Low!

Lisa Lewis, Director of the Show Low Public Library in Show Low, Arizona, knew from her community discovery that her community wanted an active learning space to support drop-in crafting programs as well as movement and balance programs. Lewis also wanted to create a space where adults and youth in the community could interact and learn from one another in a positive way. As she turned to prototyping this transformation, Lewis decided to use LEGOs, which are well suited to building models. Although the LEGO model was not exactly to scale, it was close enough to get a solid idea of what the real space would look like. Lewis engaged the youth librarian and the weekly teen LEGO Club to help create the prototype. Once community members got involved in the planning process, they became very excited about the ways that they were going to be able to use the space. According to Lewis, “Having the teens involved gave them ownership of this new space.”

Beardsley and Memorial Library Goes 3D in Connecticut

When Beardsley and Memorial Library Director Karin Taylor set out to create her library’s Smart Space prototype, she started with a desktop publishing program because it was a familiar format to begin planning the details for the space. According to Taylor, “one of the biggest challenges was deciding on what shape and configuration of furniture since the space is kind of odd shaped.” The two immovable posts that support the ceiling beams in the transformation area presented another challenge. In order to better visualize how to work around the challenges, Taylor made the move to a three-dimensional prototype to see how the layouts fit in real space. Library Assistant and project partner Carol Parent enlisted patrons who regularly visit the library to help create the model out of cardboard and construction paper, and then to provide feedback on the possible configurations of furnishings. Taylor appreciated the prototype as a “rough draft” of the main ideas they had envisioned. She learned that it was a critical exercise to experiment with a variety of scenarios of furniture types to use and to troubleshoot some of the limitations of the space before actually purchasing the items. “Admittedly I was skeptical about how useful this phase was going to be, but in the end I’m really glad we did it!”

Prototyping in Poy Sippi, Wisconsin

After Poy Sippi Public Library Director Jeanne Williamson and her project team sketched out a plan on paper, they took the next step and made a three-dimensional model. The prototype that emerged was a community effort. One patron built the foam core and plywood box to scale; the project team made the moveable furniture out of colorful construction paper, tape, yarn, and other simple materials. Once the plan came off the page and became a tangible prototype, the Poy Sippi team was able to answer some key questions about their proposed plan, especially regarding size. “When we started to make the sectional furniture to scale, we realized that it would be too big, so we went back to the drawing board and settled on two-seat and three-seat sofas. We also realized that the new tables we had previously considered would take up too much space.”

Williamson also found that sharing the prototype and talking about it with patrons increased their interest and their contributions. “During the [community] discovery, the pre-K parents wanted a children's kitchen set,” says Williamson. “After sharing the prototype with patrons, one family donated their kitchen set, which her children had outgrown. Another patron volunteered to paint a colorful mural in the area, and another will donate children’s toys. How great is that?”

A Little Help in Lopez Island, Washington

Malia Sanford, Arts and Programming Librarian at Lopez Island Library, enjoyed the time spent in the “playful prototyping stage” and created a number of different iterations of the space modeled with cardboard. A couple of those iterations were the result of a “fun, somewhat impromptu” prototyping session Sanford had with a group of tween/teen girls visiting the library. Sanford says, “I set it up as a design challenge and the group divided into two teams to design the active learning space.” They came up with some great ideas including:

- A beaded curtain for visual privacy

- Colorful area rugs of different shapes to designate separate activity areas

- Chairs that hang from the ceiling

- A sewing machine on-site

- Bean bag chairs (of course!)

- Smaller side tables in the comfy reading area (rather than one large coffee table)

Envisioning the Changes in Dodge Center, Minnesota

During Dodge Center’s community discovery and ideation phases, they learned that changes to the children’s area were most desired. The space that Ingvild Herfindahl, Director of the Dodge Center Public Library, had to work with was small, with just a table, chairs, and some toys. “Not very helpful for kids with active bodies and active minds,” reflects Herfindahl.

Prototyping was an essential part of the project to figure out what would actually fit in the space and what would have the largest impact for the greatest number of people. Herfindahl explains, “I have trouble visualizing changes, so we spent a lot of time working on this phase,” including talking to patrons, talking to staff, walking over to the space, taking measurements, putting it on paper, arranging paper cut-outs, and then rearranging them. Translating the paper plan into a scaled three-dimensional model using LEGOs helped the team get a better sense for the new configuration and its relation to existing windows, shelves, and even ceiling height. Without the model, they would not have readily visualized the whole new play area underneath the loft.

The prototype also gave the library a great tool to use in promoting the project and communicating their ideas with their community. Having the LEGO model on display allowed for the public to really understand the project and sparked excitement for the upcoming changes.

VR Prototyping in Surgoinsville, Tennessee

When Hawkins County Library Director Yvonne Woytovich and Surgoinsville Branch Manager Rachel Franklin set out to construct their prototype, they decided to go a bit higher tech. Through their community discovery process, they learned that reconfiguring the library and creating a much-needed teen area would be the focus of their transformation. However, it didn’t seem like there was any extra space to devote to this new teen area. To envision their space, Woytovitch turned to three-dimensional modeling software, which would allow them to explore a variety of arrangements without making any real changes and regretting them. She measured out the library and entered the dimensions into the computer. Originally, Woytovitch and Franklin thought about putting shelving on the diagonal, but the birds-eye view of the whole space during modeling showed clearly that this configuration wouldn’t work.

All of the staff participated in viewing the VR versions and suggesting changes to easily test. Woytovitch says, “It was so much easier and quicker to try out different ideas that way. (Think ctrl-Z.) We weren’t really limited by anything but our imaginations. And it was fun too."

A “Real-Life Prototype” in Laurel, Delaware

Rather than create a three-dimensional model, Youth Librarian Abby Davis at the Laurel Public Library took an “action prototyping” approach. Action prototyping tests how a target audience would use the proposed space by staging a simplified version of it and observing how users interact with the equipment and activities. This kind of prototyping can uncover assumptions about users’ interests and behavior and allow for course corrections before committing to the full-fledged plan and programs. Davis opened the space identified for potential transformation, provided supplies and materials for active learning, and observed the optimization of the space created by the patrons who used it. Davis explained that this approach tested how the patrons, primarily youth, would respond to having “agency over the space, grabbing materials on their own, and being responsible for clean-up.”

This real-life prototyping worked “beautifully” for two weeks before Davis encountered what she described as “slippage.” Davis says, “the storage space became cluttered as items were thrown in haphazardly. Pictures and creations were left out in the open.” Utilizing this kind of action prototyping allowed Davis to identify potential weaknesses in her project plan and reevaluate materials and storage options; things that she would not otherwise have encountered until after implementing her plan.

Prototyping is the Smart Thing to Do

The prototyping phase of the design thinking process does not need to feel daunting or burdensome. There is such a variety of forms and approaches you can use to tackle and test design challenges, and the materials used can be quite simple. Even those who believe themselves to not be “crafty” are encouraged to grab some cardboard, tape, markers, tape measure, and have fun. The benefits are many. The examples of the Smart Spaces libraries demonstrate how prototyping allows experimentation and can reveal design solutions not previously considered. It can avoid costly mistakes of remodeling or buying furnishings that turn out to not work in the space. Prototyping can test assumptions about how users will interact with a space and the equipment before implementation. And, finally, inviting community members to view, engage with, and even help create prototypes extends that all-important collaboration as co-creators of a space that is intended to center their active learning interests.

Read the three other stories in this series, summarizing the experiences of the second Smart Spaces cohort as they moved through the design thinking process:

The Smart Libraries Create Smart Spaces project was made possible by support from OCLC and a National Leadership Grant (project number LG-80-16-0039-16) from the Institute of Museum and Library Services. The Association for Rural and Small Libraries was implementation partner for the project.

Toolkit for Creating Smart Spaces

WebJunction offers a toolkit to help you re-envision your library’s place as a center of community learning. Explore more of the Toolkit for Creating Smart Spaces.