Small Libraries Discover Their Communities

Editor’s note: The Small Libraries Create Smart Spaces project used placemaking and design-thinking strategies to support libraries through a process that transformed their existing spaces in cost-effective ways and reimagined their relationship with their communities. The series of stories that follow summarizes the experiences of the second Smart Spaces cohort, who participated in 2019-2020. This first story in the series covers the “community discovery” phase of the design thinking process. For stories of the first cohort (2017-2018), see their Transformation Stories.

The design thinking process begins with a deep investigation into a community’s values, needs, and interests before rushing to develop space and service transformations. Forging connections and starting conversations with your community are essential objectives of this stage, along with exploring beyond the library walls to meet people where they are. There are a variety of strategies and tools that you can use to get to the heart of your community’s needs and interests during this discovery stage.

It seems reasonable to assume that the staff of a small-town library would know their community pretty well. Many of the Smart Spaces libraries had previously conducted traditional surveys, asking respondents to fill out paper or electronic forms with an array of quantifiable and open-ended questions—good for gathering information but not so good for putting a human face to the library and sparking relationships. The more unconventional tools of community discovery challenged the Smart Spaces cohort to think beyond the impersonal survey, get outside of the library to engage with community members, and (for some) to stretch outside of their comfort zone. The participants surprised themselves and the project team with the fresh insights they gained using these unique discovery methods.

With this range of unconventional tools as a starting point, the Smart Spaces cohort improvised and customized them to explore and connect with their communities. The following examples reveal the creative ways in which the libraries uncovered their community’s aspirations through discovery.

In La Grange, Texas, Fayette Public Library Director Allison MacKenzie took advantage of an existing event—the school’s annual “Get Set for Summer”—to collect feedback from her community, as well as talk about the library’s summer reading program. Capitalizing on the summer reading theme, “A Universe of Stories,” MacKenzie created a large cardboard rocket ship, which beckoned people to “Fuel the Rocket with Your Ideas!” In response to the question “what do you wish our library had?” and the chance to win a gift card, community members were encouraged to write any ideas that came to mind on colorful slips of paper and drop them into the rocket. This simple and playful format garnered 31 responses from parents, kids, and teens at the event, with the added advantage that MacKenzie was there to interact personally with all of them. “The responses were helpful,” said MacKenzie. “We had several requests for a coffee bar or some sort of coffee/tea station. There were some specific technology requests like tablets and virtual reality and some suggestions as simple as a rocking chair.” After the event, MacKenzie placed the rocket in the library to continue gathering feedback from patrons.

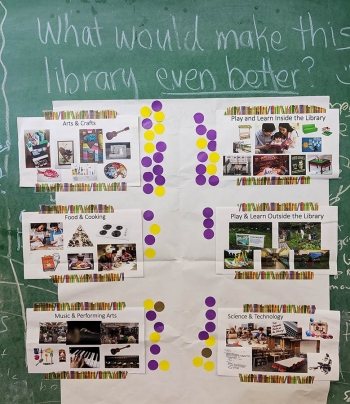

The dot board, or idea board, was a popular tool among the Smart Spaces cohort. The dot board introduced visual elements in the form of pictures or drawings that illustrate a range of choices being offered, most commonly a variety of programs the library is considering delivering. This exercise helped community members get beyond their own conventional thinking about what a library can do when they see new and unexpected ideas depicted on the boards. Voting took the form of sticking dots on the choices.

At Kauai’s Waimea Public Library, a branch of the Hawaii State Public Library System, Branch Manager Michelle Young created a colorful dot board, using photos to illustrate themes of arts and crafts, food and cooking, music and performing arts, play and learn inside the library, play and learn outside the library, and science and technology. By taking the board to the annual 4th of July celebration in Kekaha, Young elicited voting from both library patrons and those who don’t ordinarily interact with the library. The president of the local Friends group came for part of the event and encouraged two people to sign up for library cards. While Young was thrilled to learn that the areas the community voted for most were also "the ideas I'm most excited about implementing," she also was surprised to find that food and cooking was not a more popular choice.

At the Beardsley and Memorial Library in Winsted, Connecticut, the team of Library Director Karin Taylor and Children’s Department staff member Carol Parent started their community discovery with brainstorming to identify some segments of the community who do not use the library regularly or at all. Taylor and Parent hoped to “figure out some areas to target for either focus groups, community conversations, or happy hours.” They also utilized a survey aimed at members of the community who already use the library. “We absolutely want to include current patrons’ input of what they’d like to see happening here!” To collect feedback on specific program suggestions, they also created a dot board, which incorporated the American Library Association’s “Libraries Transform” campaign statements to see what library users value, such as, “libraries are more than checking out books.” Taking advantage of the dot board method’s portability, other community organizations and businesses volunteered to host the board to help gather more feedback without requiring any library staff presence.

used with permission from Beardsley & Memorial

Library

Taylor and Parent decided to take their discovery process into a favorite community event: the annual Winsted Rotary Pet Parade. The library participated with a Dr. Seuss-themed float and a mobile “Think-A-Think” suggestion box. According to Taylor, “a small group of staff went from person to person, told them about the Smart Spaces project, and asked what they’d like to learn about or participate in at the library.” Using several methods of discovery helped the Beardsley library ascertain the varied needs of their community, and as Taylor exclaims, “we are having fun with this!”

When Abby Davis, Youth Services Librarian at Laurel Public Library in Laurel, Delaware, embarked on her library’s Smart Spaces journey, she knew the library would be targeting their young adult population. The library is within walking distance of all the community’s public schools, which means it sees dozens of kids, especially middle and high schoolers, each day when school lets out. “I would love to have a designated teen space, not just a section of shelves,” said Davis.

To begin the discovery process, Davis was able to use her established connections with the community schools to learn what teens wanted from their library. She decided to take a dot board to her weekly Monday visits to the middle and high school lunch periods to gather feedback. With just three ideas on the board for students to vote on, its simplicity made it a great starting point. “New tech to use at the library” was by far the most popular choice; Davis was surprised that the Makerspace suggestion didn’t receive more votes. One unanticipated revelation during the discovery phase was how many young people she works with crave personal space. “I think this comes from unpredictable housing situations and unstable lives at home,” explained Davis. Even though they love to play together or chat while they are on the computers, they still desire quiet time and space. “It may be what they seek out the minority of the time, but when they do, they need it.” This presented an unusual challenge for the Laurel Public Library to tackle: How to balance privacy within a community active learning space?

As the Smart Spaces cohort was conducting their community discovery, some of them learned of a community need that they realized they could address right away with minimal planning, or, “quick wins.” For two of the libraries, it meant acquiring coffee makers, which made the library more hospitable and welcoming. Other ideas that were readily addressed included connecting with the home school community, removing unwanted and bulky technology, and opening up previously unused space. (For more quick win examples, see Quick Wins Through Community Discovery.)

The greatest reward of meeting and discovering the community in new ways was the shift in the library’s relationship with its community members:

“My favorite part [of the project] was actually engaging the community in re-thinking our space. Our library is fairly modern, but we knew it had space that could be better used. People were thrilled to be included and it brought about a lot of interest as the project progressed.”

“This project feels like the beginning of a much longer and bigger way of connecting to our community.”

While the discovery phase initiates the design thinking process that eventually leads to service and program changes, it arguably has the greatest and most lasting transformational effect. Putting people at the center of the process, rather than systems and policies, creates connections that will continue to carry these libraries beyond their Smart Spaces implementation and into co-collaboration with the community for all of the services and programs they offer.

Read the three other stories in this series, summarizing the experiences of the second Smart Spaces cohort as they moved through the design thinking process:

The Smart Libraries Create Smart Spaces project was made possible by support from OCLC and a National Leadership Grant (project number LG-80-16-0039-16) from the Institute of Museum and Library Services. The Association for Rural and Small Libraries was implementation partner for the project.

Toolkit for Creating Smart Spaces

WebJunction offers a toolkit to help you re-envision your library’s place as a center of community learning. Explore more of the Toolkit for Creating Smart Spaces.